WHAT WE CAN LEARN FROM CASINOS THAT WILL MAKE PARENTING 100% EASIER

I remember the first time I went to a casino. The place was filled with a sense of excitement: bright lights, crowds bustling around, cocktail waitresses happily providing complimentary drinks, and the unspoken promise of easy money. There were well-dressed men and women playing card games and having piles of chips that were worth my entire month’s salary. Over at the craps table I heard someone yell out “Little Joe” which I thought was an affectionate name for one of the dealers (turns out to mean the “four” on dice). A moment later the stickman (the fellow in the nappy vest holding a stick with which he moves the dice around the table) shouted "eleven in a shoe store" (a two on the dice), then "Big Red, catch'em in the corner" (a six on the dice), and "Benny Blue, you're all through" (seven on the dice).

This was mesmerizing, and only with difficulty did I pull away from the game to explore more of the casino.

Before long, I had wandered over to what appeared to be a small city of slot machines. These glittery chrome-plated dream makers sat in neat, long rows. Each slot was adorned with bright lights that flashed when a jackpot was struck. More attractive yet was the occasional sound of coins clattering into metal trays.

But what really made an impression on me was the crowd over in this part of the casino. At first I thought the AARP was holding a mini convention. This clearly was the place to be for the silver and blue haired generation. These gamblers were of an age, on average, that suggested an intimate knowledge of antiquity (I was in my twenties, so anyone over 60 qualified… yes, these many years later I find that observation less amusing). I was puzzled. It was two in the morning and these legions of the old guard were grimly stuffing quarters into slot machines with the determination of a brick layer.

Every once in a while the lights above one of the machines would blink brightly and a bell would briefly ring. Someone had won a jackpot! It didn’t happen often, just often enough to keep those good people awake and plugging more quarters into the slot machines.

You’re probably wondering how on earth this is related to parenting? Honestly, it has everything to do with parenting. In fact, it relates to one of the main things that you need to get right in parenting if you want to maintain your sanity while raising children.

Let me explain – this won’t take long, but it is important. And (stay with me), because we need to talk about pigeons for a minute in order to see how it applies to raising happy children.

PECKING PIGEONS AND A MAN CALLED SKINNER

In the middle of the last century, a psychologist by the name of Burrhus Frederic Skinner was very keen to study the behavior of pigeons. He reasoned that studying these animals was much easier than studying people. What’s more, Skinner also believed that the basic principles of behavior operated the same across all species (he was partially correct, but the emphasis is on partially… a story for another time).

Skinner hypothesized something about animal behavior that everyone knows already (that’s what psychologist do). Skinner guessed that if you rewarded a pigeon for some random behavior, say pecking on a lever, before long the behavior would start to happen more often.

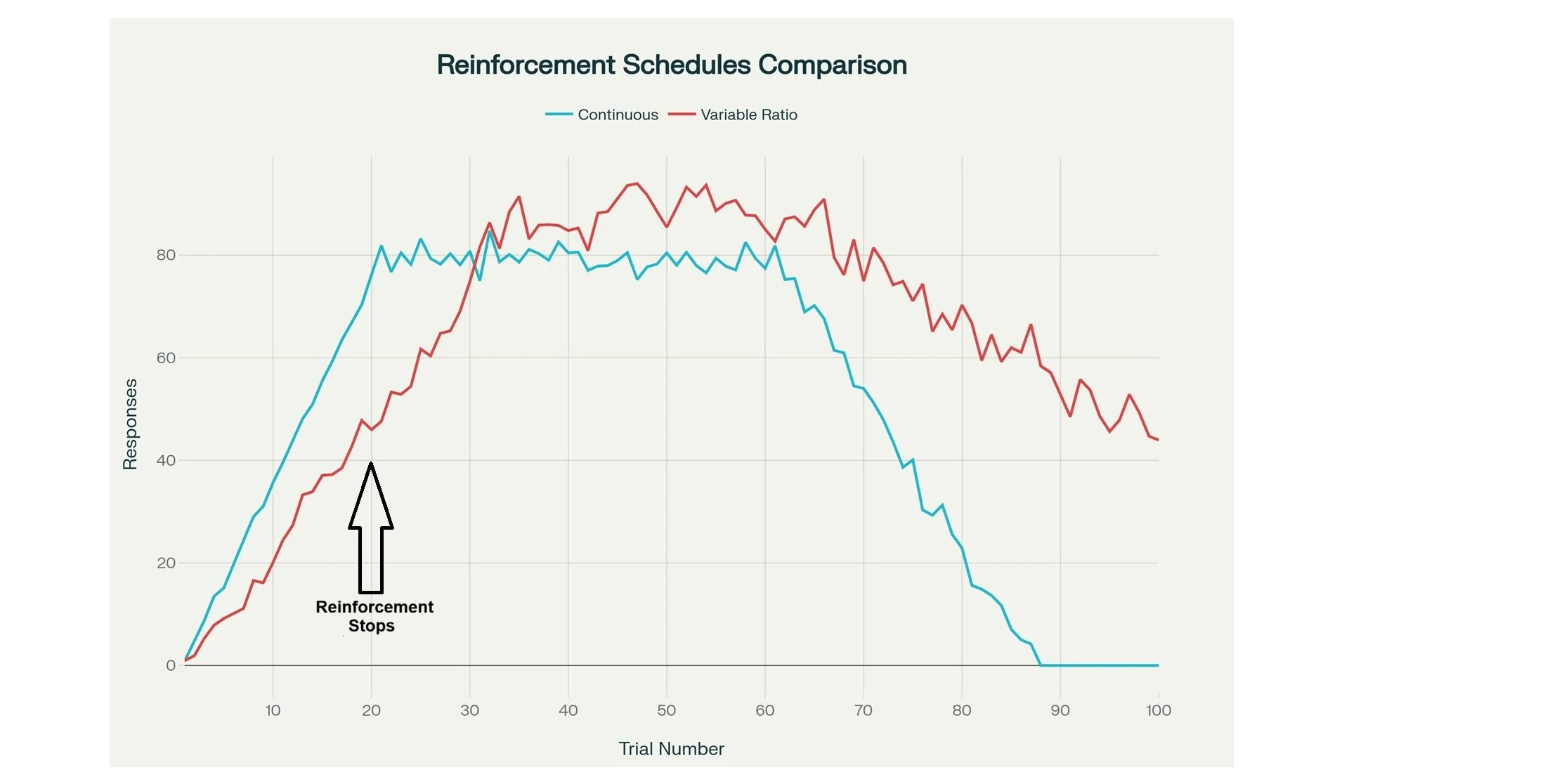

Sure enough, he found that when pigeons received a small portion of food each time they pecked on a lever, they began to make lever pecking their primary business. Peck on the lever, be rewarded with a kernel of corn. Pretty straightforward. He called this a continuous reinforcement schedule.

Continuous because a reward followed every time the pigeon performed the desired behavior.

But then Skinner got to thinking. What would happen if you rewarded the pigeons at first, and then once they learned to be expert lever peckers, you stopped rewarding them? He ran a few experiments, and it turned out that the pigeons, after no longer receiving a food reward for pecking, stopped after a short while. They gave up on lever pecking as a way to get food.

The takeaway? Even pigeons have enough smarts to know when the good times are over.

What would happen, however, if you did not stop rewarding the lever pecking altogether but just cut down on how frequently the rewards came? And to make things more interesting, Skinner thought to himself, what if you somewhat randomly rewarded the lever pecking? Maybe providing a little corn every 5 to 10 pecks. This is what Skinner called a “variable ratio reinforcement schedule.”

Variable because the pigeon was not rewarded consistently, only some of the time and when the reward would come was unpredictable (i.e., variable).

Under these conditions, the pigeons began to peck the lever like never before. They became obsessed with getting their beak on the lever to get more food.

It was as though the pigeon was pecking away, thinking, “What, four pecks and no food? Maybe another four pecks will do the trick, I never can tell for sure. Curse that madcap scientist Dr. Skinner!”

The birds increased the frequency of their pecking because it was impossible to tell precisely when there would be a payoff. They had learned, however, that with persistence, a payoff would surely occur.

Now this got Skinner to thinking even more. What would happen when you stopped rewarding pigeons under these conditions? That is, what would the birds do who had been trained on a variable reinforcement schedule once they stopped getting any rewards at all for their lever pecking behavior?

It turned out that they continued to peck on the lever for a much longer period of time when compared to birds that had been trained on a continuous reinforcement schedule. Much longer. Not even a contest.

This makes sense, right? Because the rewards no longer came predictably. The pigeons on the variable reinforcement schedule had been trained to persist in the face of adversity. They had learned to expect that if they just kept doing the same thing over and over, food would eventually fall from the heavens into their cage.

The birds on the continuous reinforcement schedule learned to expect an immediate reward, so when that did not materialize, they quickly realized that more pecking would not help (See Figure 1).

Now, replace the bird with a child, and the reinforcement (reward) of bird seed with parental attention, a child getting his/her way, or some other desire a child has, and you can see how this applies to parenting.

TAKE AWAY MESSAGE SO FAR…. Schedules of variable reinforcement create exceptionally strong responses that are not easily changed. In fact, there is an interesting twist that comes when you stop rewarding behavior under these variable reward schedules. The frequency of the behavior usually increases, and becomes more intense, once you stop the rewards. This is true not just with pigeons, but with people as well.

If the reward continues to be withheld, the behavior will almost always eventually stop. But when compared to continuous reinforcement, it takes a much longer time.

BACK TO CASINOS AND SLOT MACHINES

Let’s look again at the people playing slot machines at two in the morning. What schedule of reinforcement do slot machines follow? Yes, that’s right, a variable schedule of reinforcement. They don’t pay off every time, nor on a regular schedule, but rather every so often in an unpredictable way. (In fact, I cannot think of any form of gambling that does not follow this schedule, although some do so more than others).

There is a reason why casinos make a lot of money. They know how people respond to reinforcement schedules. The person at a slot machine is going to keep playing because he, or she, has already had a payout (or seen others get a payout) and feels certain another is right around the corner. They know for a fact that slot machines are unpredictable, so even though they have lost some money already, why shouldn’t the next quarter provide a big payout? The money they have already put in is just an investment in a jackpot that is likely to occur very soon.

Compare that same person an hour later. Imagine that Eunice and Sherie have called it a night. They leave the slot machines and take the elevator up to their room. But before getting there they stop to get a soda from a vending machine. Eunice needs quarters (she spent them all on the slots downstairs), so she puts a five-dollar bill in the change machine that sits next to the soda dispenser.

The machine makes a whirling sound, sucks in her five-dollar bill, and…. nothing. No coins come tumbling down into the little change tray. No satisfying clank of quarters piling up. The only thing Eunice hears is the hum of the ice machine.

Now let’s freeze the action at this point and step back for a moment. What do you imagine Eunice will do at this point? Will she feed another Lincoln into this bad boy hoping for a big payday? Will she whisper to her friend Sherie “I’m feeling lucky? This next bill is going to pay out big time!”

Pretty unlikely. Eunice knows what to expect from a change machine. You nearly always get out what you put in – and if that does not happen then there is no need to keep trying. Game over. Eunice will not treat the change machine the way she treated the slot machine because she knows what to expect. Change machines operate on a continuous schedule of reinforcement. Put a bill in, get quarters out.

PARENTING AND MINIMIZING STRUGGLES WITH CHILDREN

I’m sure we can all see how this applies to parenting. But stay with me while I briefly flesh out the application of this concept.

One of the things I frequently see when working with parents (and something I have done as well) is to inconsistently apply household rules. When we, as parents, are inconsistent, we are teaching are children to respond to a variable schedule of reinforcement. Normally a bad idea.

An example comes to mind. Three-year-old Jennifer likes to whine when she cannot get her way. Mom and dad both work, so they don’t have a lot of time on work days to spend with their daughter (they both feel guilty about that as well). When Jennifer whines about needing to follow her parent’s directions, their initial response is to insist that she do as they have instructed.

But Jennifer is young, and she responds by whining some more. A struggle ensues. Sometimes mom and dad prevail, and Jennifer does as she was told. Sometimes they give in. When they give in to the whining, Jennifer gets to avoid doing that which she objected to (that is a reward in itself).

They have set up a variable reinforcement schedule. They have become human slot machines. Jennifer’s whining is similar to the pigeon pecking a lever. The reinforcer (like the food for a pigeon) is their daughter getting to have her way. She may not get her way most of the time, but she wins often enough to know that whining leads to rewards (getting her way) some of the time.

Over time, mom and dad will notice that their little girl has become a handful. That she is extremely defiant. My way or the highway type of defiant. So, the parents decide enough is enough, from now on she has to obey (they will act like the change machine – predictable, and consistent).

They start this new approach and Jennifer’s whining increases! (Remember, we expect this when breaking habits formed with variable reinforcement). They doggedly persist for two or three days but things get worse (something else we expect when coming off a variable reinforcement schedule).

But they don’t persist long enough. Their daughter’s increased whining convinces them that they are doing something wrong. Doubt and stress build. They wonder if this approach just won’t work for her. Eventually, mom and dad give up.

Now their daughter’s variable reinforcement schedule is even more deeply rooted than before.

SOLUTION

There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution, but there is a general approach that works for most parents.

First, count on it taking longer than you expect to break habits that have been formed through variable reinforcement schedules. For some children it may take a week, for others a month or more before progress is seen.

Second, don’t let your child’s reaction cause you to get sucked into arguments, long explanations, or angry outbursts. Calmly state what you expect, repeat it once or twice if needed, and otherwise do your best to ignore the child’s tantrum. (Some tantrums cannot, and should not, be ignored but that is another story for another time).

Third, consider setting up a reward for appropriate behavior. For example, if your child normally responds by having a tantrum when you ask him, or her, to take a bath, try providing a small reward when they comply. You may want to create a reward chart and when your son or daughter obeys a bedtime direction, a start is placed on the chart (after the age of 6 or 7 years children don’t care about receiving stars…. So don’t try this with older children, they will think you’ve lost your mind). Keeping a box of stickers and letting your child pick a sticker if he or she follows your directions is another approach that is often helpful. Obviously children of different ages require different types of incentives. None of which need to be elaborate, just as long as they are meaningful to your child.

The big payoff for consistency is not just less stress for you and your child. There is evidence that consistency also leads to children being less likely to become depressed or anxious.

CONCLUSION

Variable schedules of reinforcement powerfully influence behavior. Although we’ve not covered it in the above discussion, these schedules can be used to promote healthy behavior as well (think of how you have learned to persist in pursuing a goal despite setbacks, knowing that victory is not always reached on the first, second or third attempt).

As parents we can easily slip into creating a variable reinforcement schedule that ends up causing all kinds of headaches for ourselves, and our children. In fact, I think every parent does this from time to time… don’t beat yourself up if you realize you’ve fallen into that trap.

These schedules, and the behaviors that go with them can be changed. They are not written in stone. If we think carefully about how we would like our children to respond, provide some rewards for their compliance, and show persistence in our expectations, success nearly always follows.