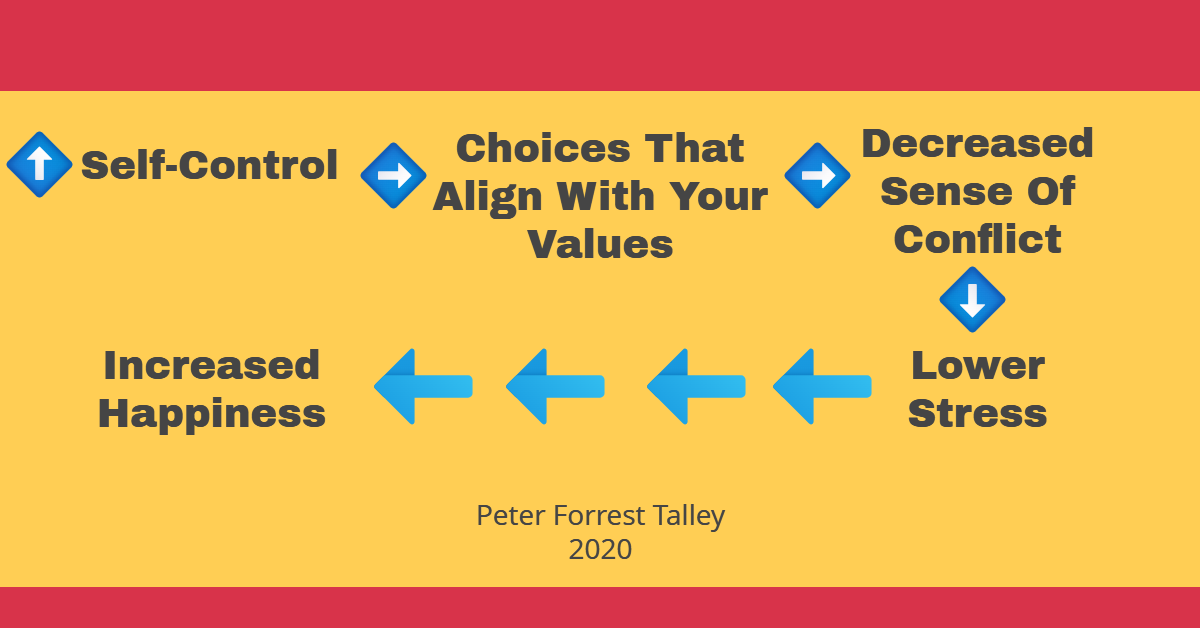

Research at the University of Chicago conducted by Wilhelm Hofmann and colleagues found that people who exercise greater self-control are happier than people who show less self-control.

Even though this finding is correlation, and therefore does not prove a causal connection, it still strongly points in a causal direction.

It is similar to finding that people who have strong social skills have more rewarding friendships. Is it logical to believe that social skills assist in developing rewarding relationships? Of course.

But what is the logical connection between self-discipline and happiness?

Glad you asked. Researchers found that more disciplined people generally engage in activities that are consistent with what they consider to be appropriate. By comparison, those who are not very disciplined are more likely to engage in activities they believe are inappropriate.

As a result, men and women who exercise less self-discipline are frequently in a state of internal conflict (over doing what they know is wrong). More disciplined individuals avoid such internal conflicts and consequently are happier.

My experience from having worked with hundreds of hurting people aligns well with this conclusion. It is not uncommon for me to see men and women whose depression or anxiety is, in part, related to a lack of self-discipline.

To be clear, it’s not a matter of them consistently behaving immorally even though they know better – far from it.

Instead, it is that their failure to use self-control causes them to make decisions that keep them from reaching the goals they value most. This, in turn, causes them to live a less-than-fulfilling life.

Over time they stop growing, become hesitant to dream about the future, and the excitement for life that once filled them ebbs away. This opens the door for the eventual onset of anxiety and depression.

What Gets In The Way Of Building Self-Control?

There are many culprits we could point to when looking at barriers to self-control. That sort of exhaustive review, however, would not be helpful. Let’s instead just look at two very common obstacles.

The first is that we live in a much more self-indulgent time than in the past. We don’t need to idealize the past to realize that modernity has made many tasks so easy to accomplish that daily living no longer requires the same level of discipline as it once did in order to enjoy life’s pleasures.

From our present-day vantage point, we may look back and see the day-to-day challenges of the past as arduous; they also carried the benefit of requiring one to exercise self-control.

For example, just 20 years ago, one needed to go to a movie theater to see a movie, or wait many months (or years) for its release on television, or go to a movie rental company (e.g., Blockbuster). Only in 2007 did Netflix begin to offer movie streaming. Today, you can pull up any one of literally thousands of movies to view within minutes of sitting down in front of a large flat screen television.

Another example is taking and sharing photos. In the past, taking a photo required buying film, bringing a camera, snapping the photo, and sending the film to be processed. Some days later, you were rewarded with seeing the photos. If you wanted to share your pictures, you then needed to send off the original (leaving you only the negative), or get the photo duplicated and wait several more days for it to be produced.

It wasn’t until the end of the 1990’s that this changed, at least in a way that most people could afford. Technology continued to advance, and today people think nothing of snapping a photo with their phone and sending it to whomever they wish.

Again, the ease with which we can now acquire sought-after items and experiences means that people no longer have as many naturally occurring opportunities for self-discipline as in years past. Such effortless acquisition does not build the mental strength needed to exercise self-discipline.

The most formidable challenge to developing self-control, however, lies within our very nature. It is as ubiquitous as gravity. We are inclined to put off the hard work required for a better future in favor of an easier path that leads to immediate rewards. We trade the gold that can only be grasped by sustained effort and sacrifice, for the nickel and iron that lie within easy reach above ground.

Research on expertise reflects this tendency and illuminates its impact. A terrific example is found when examining how violinists approach practice. Researchers found that virtuoso violinists (those in the top 10% of their field) practice much differently than their lesser accomplished peers. They spend the majority of their time mastering skills that cause them to struggle. Practice focused on challenging their weaknesses. This is called deliberate practice.

Less accomplished violinists, however, focus the majority of their time playing musical compositions in which they already had strengths.

Virtuosos took the harder path to perfecting their skills.

Again, it is a natural human tendency to be drawn toward the easier path. This is appealing because it is less frustrating, requires less patience, and much less self-control.

The cost of taking this path is heartbreaking: remaining stuck in the rut of mediocrity.

This tendency creeps into nearly every facet of life: professional activities, relationships, personal fitness, religious practices, etc. It is a part of human nature that must be pushed back against if we are to reach our full potential.

Self-discipline is the antidote to this part of our nature.

How To Strengthen Self-Control

I have often heard someone say “I just can’t help but…” fill in the last part of that sentence with some behavior that occurs when self-control fails.

But when I ask the person if they would have been able to do that which they tell me was impossible, were someone to have offered them a million dollars, they respond “Yes, for a million dollars I absolutely could have done so.”

The takeaway lesson: that individual had the ability to exercise discipline, but chose not to.

Self-discipline was available, ready to be used. The person chose not to do so because the rewards were not high enough until a million dollars was offered.

That is not a lack of self-discipline but a lack of motivation.

And here we come to an interesting conflict regarding how to think about motivation. Some argue that motivation is basically a feeling. That is, how strongly does one feel about achieving some goal or outcome?

A moment's reflection will show that motivation cannot be simply a feeling.

If feelings are the basis for motivation, then mothers and fathers who experience a strong feeling to be free from parental obligations should be considered highly motivated to leave their children. Yet most parents have times when they very much desire to be free from the demands of parenting, but continue to perform their caregiver duties with great fidelity and consistency.

If we define motivation as a feeling we would then conclude that these mothers and fathers are highly motivated to leave their children – yet they do the opposite. This makes no sense.

Motivation cannot be just a feeling that has the final say regarding how we behave. Feelings are not the same as motivation.

If we think of motivation instead a commitment to achieving some goal or outcome, these problems fall away. An example of this can be seen in the husband who travels for a business meeting. He and his wife have had a difficult relationship for several years. Their marriage is in serious trouble.

While away at this meeting, the husband meets an attractive colleague who works for the same business but in another state. The two are strongly drawn to one another. A day of meetings followed by dinner gives them a chance to know one another better.

Eventually, the woman suggests that they spend the night together. His wife would never know, and they could enjoy a period of sensual bliss with ‘no strings attached.’

The man finds the invitation extremely enticing in some respects (this is the feeling side of things), but instead of accepting the offer, he immediately declines, goes to his hotel room, and makes plans to avoid interacting with the woman as much as possible. He does not wish to be tempted.

He would confide, if asked, that the decision was not difficult. A strong commitment to his morals, including being faithful to his wife, motivated his actions.

If we judged his motivation by using feelings as our metric, we would conclude that he was highly motivated to have an affair. But his actions suggest the opposite.

He was highly motivated not to have an affair. Motivation was not a feeling but a commitment attached to a value. The value was being true to his moral compass, and his commitment was directed at achieving this end.

The practical application of this insight is straightforward: if you wish to improve your self-discipline, you need to prioritize your commitment to pursuing what you value. Not just moral values, but all types of values that are attached to what you wish to make of your life.

If you highly value good health, you will need to commit to proper nutrition and exercise.

Is what you value related to professional success? Then this becomes a target upon which to harness your commitment to behaviors that align with reaching that goal.

Knowing what you value is essential (think back on the research results mentioned at the start of this article, and how self-control led to greater alignment between behavior and values, and this correlated with increased happiness).

After having taken an inventory of three or four areas of your life and the values attached to each, choose just one of these to focus on for the next several months. Ask yourself what your behavior would be like were it perfectly aligned with your values. Then compare that to how you currently behave.

If there is a discrepancy, make a plan to close that gap and consistently apply yourself to doing so.

When you have succeeded with this one area of life, move on and use the same approach with another area of life. As you progress, you’ll find self-discipline becomes easier, and in many ways automatic.

Conclusion

Self-discipline is like the rudder of a ship, keeping the vessel on a specific heading. The captain determines the destination, but without a rudder, the ship is pushed hither and yon by whatever currents and winds it encounters.

You, too, can steer your life in exciting new directions by exercising self-discipline. This is the first and essential step - gain control of the rudder. Build up your self-discipline, and you’ll be astounded by what you can accomplish.